(1910-1988)

Born in Newport, Kentucky in 1910. Grew up in Cincinnati. Graduated from Woodward High School. Received bachelor’s and medical degrees at the University of Cincinnati (MD, 1935). Married Virginia Raphaelson in 1936. Five children: Steve, Nancy, Mark, Richard, and Ed. Served two years as major for Army Medical Corps in England during WWII (1942-1944). Established Department of Radiology at the University of Cincinnati Medical School where he served as professor of radiology from 1951 to 1983. Director of radiology at Cincinnati General Hospital from 1951 to 1973. World renowned chest radiologist. Made many medical discoveries and was lionized as a lecturer. Died of a heart attack in 1988 while working on a manuscript.

Related documents:

- Excerpts of Ben’s war letters

- War letters of Ben Felson

- An essay on Ben’s professional life, by Frank Gaillard

Biography

BEN FELSON, The Early Years, by Marcus Felson, June 2025

I am now 77 years old. I have a good memory but the fragments resurface in an imperfect order. This is my first try at writing a memoir of my father, Benjamin Felson. He was known as Bennie when young, and Ben later, but his siblings and old acquaintances still called him Bennie. I don’t remember whether they spelled it Benny or Bennie, but it doesn’t matter since it was not mainly for writing.

He was born in Newport, Kentucky, right across the Ohio River from Cincinnati. The Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe were too poor to move to the slums of Cincinnati in the first round, so they went to Newport. After a few years the Felsons had enough money to move to the slums of Cincinnati. They moved to the West End between where Findlay Market and the Music Hall area are today. In time the family started payments for a house in Addyston, Ohio, a western suburb along the river, but they lost that house in the Great Depression. They also faced floods and fires. Eventually they moved up the hill to South Avondale.

Ben was one of eight, nine, ten, or eleven. Eight who lived and whom I knew. Nathan who died as a young boy. In addition, there were one or two stillbirths. Ben was in the middle and was a kind of star, effervescent, attractive to adults, backslapping, fun, smart, witty, fast, and an excellent athlete. Even as a child, by many reports, he was already charismatic. His athletics were largely informal, since he did not have time for organized school activities. However, the Felson boys were members of a named group, the Ajax, which played other groups of boys in baseball and basketball. My father told me Irv and Chippy were the best athletes in the family. But he was very good. He could also run fast, which helped when the bigger kids in the tough neighborhood were chasing him.

As an adult he played in the Jewish Center softball league, which exists to this day. He was not a power hitter. He was great at the plate in placing a ball for a single. He knew all the fundamentals. He ran fast. He knew the poker side of the sport. I remember his last day. He was past 40 already and one of the oldest in the league, playing with largely young men. He ran in to score and broke his arm. Later, my brother Ed, playing in the same league, on one great day had four hits, scored twice, caught a great catch and then won the game for the team. When the game was over one of the older guys who had played with Ben came over and said, “Great game, Ed. But you’ll never be as good an athlete as your father.”

Ben discovered how to apply his skills early on. For reading, he did not pick the hardest and thickest book but rather started in his school library with A and read the books one after one until he reached the middle of the alphabet and was ready to move on. They were ordinary books. He thought one could learn from any of them and so he tried to read all of them. His younger years were spent at Raschig school, which may have been 90% Black when he attended. I looked it up and found this picture:

He worked in a drugstore and read between customer arrivals. He had a great power of concentration, including in noisy places. His customers were from many backgrounds and many were Black. He learned at an early age to be racially tolerant. He said that some black customers would arrive and see him reading or studying, then leave him alone and wait rather than interrupting him.

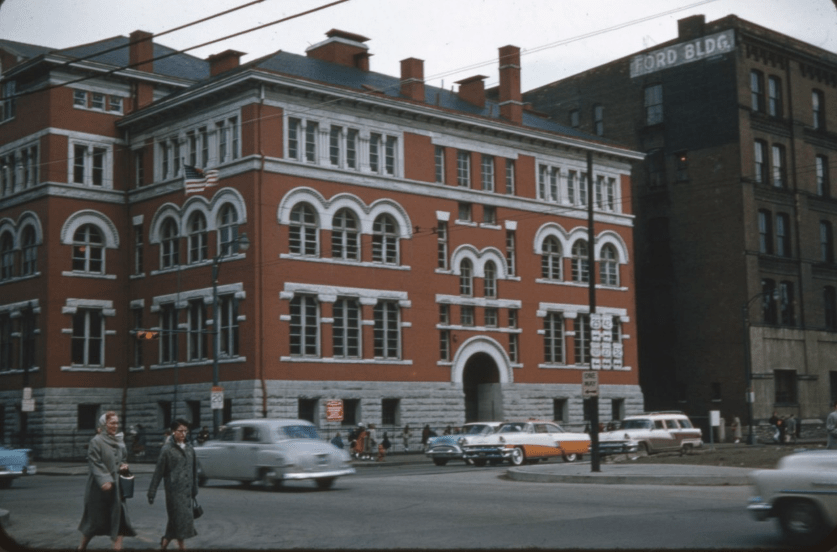

He went to old Woodward High School, located in the same area (picture below). It is called old because a school of the same name was built in Bond Hill, then the suburbs, and the old one closed or converted. I suspect he walked to both schools. The poor kids, including him, would ride for free by holding onto the back of the streetcar. (I found out lately that this is called “skitching, requiring skates or snowy weather to make sneakers slide.) It was dangerous. Also, from time to time the conductors would stop the streetcar and chase the kids away. So they had to wait for the next streetcar.

I also know that he would sometimes sneak into Crosley Field, not far from where he lived and went to school. At that time an adult was allowed to bring his young son in for free, so Bennie would find a suitable adult waiting in line and ask to be his son for the next few minutes, then get in for free. His other technique was not so successful. The local boys knew which of the two spokes in the iron fence in the outfield were crooked enough to allow a slim youngster to slip through and enter for free. However, Bennie’s behind proved too wide and he got stuck. A photographer caught the scene from the rear, and the next morning, the Cincinnati Enquirer published that picture. Unfortunately, Walter recognized who it was, despite the angle, and afforded his own corporal punishment. Bennie was not nearly as close to Walter as to Chippy, and I wonder if that was the reason.

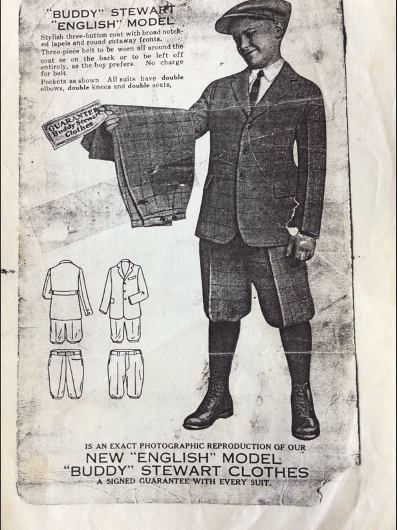

As I noted already, Benny was always a star. Always charismatic. Always stood out to teachers, adults, and even strangers. He was recruited to model clothes for an advertising photographer.

His teachers loved him, and I am sure he was a teacher’s pet. He managed to get along with the other kids. He was a master at getting his way. I once read an old book on “social control” by Edward Alsworth Ross (1901), who listed a score of techniques for influencing another person. I realized my father used all of them. He got his way, usually without acrimony. Not that he was subtle, since he was so insistent. My joke is that Walter would say, “Do this,” while Ben would say, “Why don’t you do this?”

My father was a natural at learning everything but how to pronounce a foreign language. That was perhaps because his teachers were Cincinnatians who had never roamed very far. He learned Spanish with an atrocious accent, but was able to stumble through it and with sheer insistence to make himself somewhat understood. During World War II he learned passable French, he said, and I don’t doubt it. His main language skill was Chutzpah.

My father had an ear for music. He remembered enough of the classical repertoire to identify what was on the radio. He did not read notes or play an instrument. His classical taste was the standard melodic pieces, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, etc. He also liked the odd East European sounds of Russians and Bohemians. Bach was too regular for his preferences, but I think he liked the Brandenberg Concertos. He did not normally listen to popular music. He liked opera and he and Virginia would regularly go to opera (summer) and Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra (winter). He listened. The radio was on at home from 7pm through midnight, the classical station only.

He did not appreciate jazz, except for Gershwin songs and symphonic poems, etc. When Ed became a jazz musician, he was supportive but not head over heels in enthusiasm. He tried not to be heavy handed with his children, but . . . Ed tells a story something like this. At 18 or so he said, “Dad, I’m moving to New York to become a jazz musician.” Dad said, “Whatever you like, son, it’s up to you.” A few years later, “Dad, I’m moving to Boston to go to the Jazz program at New England Conservatory.” Dad said, “Whatever you like, son, it’s up to you.” Then Ed told him, “Dad, I’m moving back to Cincinnati to go to law school,” and Dad said, “That’s GREAT.” Ben did not refuse to give his opinions, but he camouflaged them a bit.

I remember Nancy wanted to marry Roderich. I had never seen a more worried Ben before, pacing the house. But he put up with it. And he grew to accept Roderich as his son-in-law.

I also remember when Steve wanted to attend Harvard, which had admitted him. Dad told him not to go but to stay home and be a big frog in a little pond rather than a little frog in a big pond. Later, when Steve came back to Law School at the University of Cincinnati, he was first in his class and editor of the law review. Dad was often right. Most often his judgment proved correct but it took me and others time before realizing that was so.

My father finished high school two or three years early and entered the University of Cincinnati at age 15. I don’t recall what ages he skipped. He did not do formal high-school athletics partly because he was smaller than the other kids in his class, even though as big as the other kids his age. He finished college in two years and was in medical school at age 17. He was so young as a doctor and had such a baby face as an intern that the patients said, “Don’t let that kid touch me.” His medical brilliance did not extend to all its fields. He was no good as a surgeon due to clumsy fingers and fidgeting. It seems contradictory that he could hit a baseball but be unable to hold a scalpel and cut into tissue.

Ben was a general intellectual with a very focused career. He read the newspaper every morning, paper version, and kept up with sports. His great memory helped him. He stopped reading on general topics after college and focused on medicine and surrounding scientific topics. However, he did not forget his reading – even things he read decades before.

Why was he a great radiologist? Great ability to synthesize information. Great ability to break down a complicated topic into its simplest elements, then to communicate these to all – including the best and worst students. Great at telling you something in a way you would remember it and that he himself would remember it and draw upon it when he needed it. Great curiosity. He wanted to know it. He wanted to do it. He wanted to teach it. His drive was followed by more drive. Ambition was combined with enthusiasm and curiosity.

He did a year in pathology before discovering radiology. That helped him. Pathologists touch the cadaver and all its parts and dimensions. Radiologists look at a picture of the body in two dimensions – in those days there were no three-dimensional CT scans. So he figured out how to work back and forth between the three-dimensional reality and its two-dimensional depiction. And he knew how to communicate this. He’d always find and return to the fundamentals. He knew the complexities but did not get lost in them. He always considered principles more important than details or facts. He tried to go back and forth between a principle and an example, then on to another set of principle-examples. He tried to make the fragments part of a whole that was teachable and that could be remembered later.

A word about his writing. He would rewrite every sentence about fifteen times. He made it better and better. He did not stick with a suitable word but looked for le mot juste. He used the thesaurus. He made every sentence flow. In his later years he no longer needed fifteen drafts but still rewrote and honed his communications. When he gave a talk he used brief notes – not every word. He might write out a dozen words to prompt his memory. When he got very old, he was still a good speaker but I think he needed more notes to jar his memory and keep him from forgetting a term. He used humor in his talks to engage his audience and assist them in remembering. He preferred humorous anecdotes to “jokes,” and wanted each funny anecdote to reinforce a scientific point, not to distract the audience but rather to reinforce its knowledge.

I have neglected my father’s years in the Army during World War II. His war letters give his own view of his experience at great length. I call special attention to three parts: his reconstructed account of D-day; his stopping a potential race riot; and his bucking heads with Army protocol. I have not gone into great detail about his siblings. I believe he was closest to Chippy, who lived only a few blocks away and who seemed to have been his favored older brother. He was a bit more distant from Walter and Sophie, but they were communicating fairly well and Sophie was his secretary for decades.

Interestingly, during the McCarthy Era in the 1950s, somebody made secret charges against my father, accusing him of being a Communist and trying to prevent his assuming the department chair. His colleague Dr. Johnson McGuire was a southern gentleman who asked a friend who was an FBI agent to clear him. It worked.

Briefly before World War II my father worked in private practice. The first stint was in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where Steve was born. The second stint was in Indianapolis, Indiana, where Nancy was born.

My order is not perfect, but this gives you a picture.